Author:

Lutz Pietschker

Version: 2017-05-28

Home Page | Hiking | What's New

Summary:

Please do not consider this as a fixed route you need to follow; I did not, either. Rather, it is the sum of several walks I took on two visits to Saint-Nazaire in 2002 and 2013. I tried to put together a route that touches the points I personally found most interesting, so it is a very subjective selection. There are many more things to see in Saint-Nazaire, along the coast, and in nearby Nantes, but my own trips were originally concerned with the British raid on Saint-Nazaire in 1942 (Operation Chariot), so the things I visited are mostly in the area of the harbour and the old town.

A note about the images: These are all my own, but they are a mixture of original digital images (mostly from 2013), images scanned from prints (from 2002), and even photos of photos in public exhibitions. Accordingly, the quality of the images varies a lot.

Further information:

Hints:

Preface

There is a boardgame called Raid on St. Nazaire, published in 1987 by the Avalon Hill Games Company, USA. The game simulates, accurately and in great detail, the British raid on March 28th, 1942; it was this game that started my interest in "Operation Chariot" which lead, eventually, to my two visits to the town in 2002 and 2013. Just in case you are interested, I have written a review of the game, and I have also written a battlefield walk page addressed specifically to those who know the game, with references to the numbered map areas. The main land combat action in Operation Chariot has taken place in the area of the harbour and the Old Town. The image to the right shows the game board on the background of a satellite image; you can see that the game board is a beautiful and very precise map!

There is a boardgame called Raid on St. Nazaire, published in 1987 by the Avalon Hill Games Company, USA. The game simulates, accurately and in great detail, the British raid on March 28th, 1942; it was this game that started my interest in "Operation Chariot" which lead, eventually, to my two visits to the town in 2002 and 2013. Just in case you are interested, I have written a review of the game, and I have also written a battlefield walk page addressed specifically to those who know the game, with references to the numbered map areas. The main land combat action in Operation Chariot has taken place in the area of the harbour and the Old Town. The image to the right shows the game board on the background of a satellite image; you can see that the game board is a beautiful and very precise map!

Facts and History

…a rather arbitrary selection of things I found interesting. More facts will be mentioned in the main text.

_v2.svg.png)

Sections of the town walk:

Clicking a thumbnail opens the image in this window; in most browsers a shift-click will open the image in a new window.

The Saint-Nazaire town hall

A view from the town hall to the North, along the Av. de la Republique

This is what most of Saint-Nazaire looked like in May 1945 (Place Marceau, now site of the Ruban Bleu shopping centre).

Many streets in Saint-Nazaire look like this one.

Historic, or re-built in the original style? Anyway, much better.

Rather arbitrarily I choose the town hall as the starting point of this route; it is a modern building, like most of the town's buildings– about 85% of the buildings in Saint-Nazaire were destroyed in World War 2. When the town was re-built after the war, much of it was, of necessity, built fast and cheaply; many of these buildings are not much to look at, but by and by the town tries to improve on the rather drab picture some of its quarters present. With good success, in my opinion; we will come back to this topic over and over. The (French) blog of Riko St. Naz has a lot of information about the development of Saint-Nazaire, I recommend it highly.

The town hall was completed in 1960; it looks out on the Avenue de la Republique, a main axis of the town and an important shopping street, running roughly north-and-south, from the town hall all the way to the railway station.

To begin with my walk, I go south along Rue Jacques Jollinier, past the botanical gardens, to reach the Boulevard du President Wilson and the long promenade that runs parallel to the long beach.

Boulevard Wilson, the beach promenade and the AEF monument

The beach, looking westward towards Villès-Martin

As this postcard from 1900 shows, the Saint-Nazaire beach has been a tourist attraction for a long time.

Old views of the beach promenade and Hotel Wilson

Hotel Wilson

being renovated

Another building that survived World War 2

Out in the surf is a monument for the U.S. troops of the American Expeditionary Force that landed here in 1917 to help France and Britain in the Great War. On this picture you can see the troops marching on exactly the promenade we are on. The boulevard itself was named after the president of the USA who, rather reluctantly, agreed in 1917 to send US troops to Europe. We will see another trace of this event later on this walk (le frigo).

To the right and left is a long sandy beach and a beach promenade. This beach, more or less directly adjacent to the town centre and completely open to the South, is alive with Nazairiens and tourists in summer, something that has not changed over more than a hundred years. This beach stretches for more than 2 km to the West, and right up to the harbour jetties to the East.

Going eastward along the boulevard we see some of the very few real old buildings of Saint-Nazaire, for example the Hotel Wilson that has been renovated recently.

War victims memorial

The memorials at the Place du Commando (now relocated to the old mole)

RMS Lancastria memorial plate

Operation Chariot memorial plate (the chariot logo resembles the statue of Boudica in London)

t

t

The 12-pounder gun of HMS Campbeltown (now relocated to the top of the sheltered lock near the east entrance to the Saint-Nazaire basin)

28 March: Op. Chariot remembrance day

In 2013, Bill "Tiger" Watson (centre) attended the ceremony as one of the last original participants of the raid.

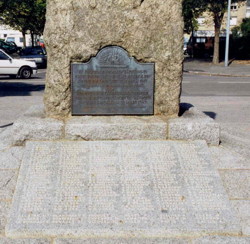

Towards the end of the beach ends we come across three more war memorials: First a sculpture dedicated to the victims of both world wars, and then, at the Place du Commando, a site with the Operation Chariot memorial and with a memorial plate for the victims that died when RMS Lancastria was sunk on 17 June 1940 .

As I mentioned, Op. Chariot was the event that brought me into contact with Saint-Nazaire initially, and my more recent images were taken when I attended the remembrance celebration on 28 March, 2013, so I will dwell on this raid for a moment before I continue my sightseeing walk.

Operation Chariot was the code name for a joint forces raid against the Louis Joubert dry dock in Saint-Nazaire, also known as the Normandie dock. The destruction of the dock was deemed necessary to discourage the German navy from relocating their battleship Tirpitz into the Atlantic, as it was the only dock on the German-occupied Atlantic coast big enough for such a ship; destruction of this dock would deny the Germans a repair facility for Tirpitz. Besides, it was a time when the British people, government and armed forces urgently needed encouragement in the war against Germany. After a series of military setbacks, the success of an offensive action would raise morale; this was, at least, a secondary consideration in deciding upon the raid.

Operation Chariot was the code name for a joint forces raid against the Louis Joubert dry dock in Saint-Nazaire, also known as the Normandie dock. The destruction of the dock was deemed necessary to discourage the German navy from relocating their battleship Tirpitz into the Atlantic, as it was the only dock on the German-occupied Atlantic coast big enough for such a ship; destruction of this dock would deny the Germans a repair facility for Tirpitz. Besides, it was a time when the British people, government and armed forces urgently needed encouragement in the war against Germany. After a series of military setbacks, the success of an offensive action would raise morale; this was, at least, a secondary consideration in deciding upon the raid.

Planning started in January 1942, and tidal conditions gave 28 March as a possible execution date. Not much time for planning and providing the forces, indeed; while the commando soldiers were available at very short notice, having kicked their feet for some time now in training camps without seeing real action, the part the Royal Navy had to play could have used a bit more time. In the end, they managed to put together a force of one swimming bomb, an outdated lend-lease destroyer named HMS Campbeltown with 4.5 tons of high explosive hidden in its bow, and a flotilla of 17 small boats (most of them Fairmile B motor launches) to transport some of the commandos and to bring Campbeltown's crew back. About 600 soldiers were involved directly, about half of them commando soldiers (who were asked before the raid whether they wanted to participate) and the other half Royal Navy officers and crews (who were not asked). Two more destroyers (Tynedale and Atherstone) operated as covering forces for the flotilla on its approach and return voyage. The raid commanders were R.E.D. Ryder for the naval force and Charles Newman for the commandos; the commander of the all-important Campbeltown was S.H. Beattie.

The project suffered from a mismatch of very ambitious objectives and available forces; in particular, the motor launches were not able to withstand any sort of gunfire and, having petrol engines, were almost guaranteed to catch fire if hit. Surprise, a series of deceptions and an "impossible" approach route across the mudflats in the southern part of the Loire estuary enabled the force to run into the Saint-Nazaire harbour area unchallenged; Campbeltown rammed the southern gate of the Normandie dock and was scuttled in place. The commandos transported on Campbeltown were able to destroy additional dock machinery to render the dry dock inoperable. However, the forces on the "little ships" suffered heavily as most motor launches were set on fire, exploded or sank by the fire of the dozens of German guns in the harbour area. Most commandos on board of these boats never made it to the shore, and few of the boats returned. In the end, only about a third of the soldiers and sailors returned to England, 169 were killed, and the others went into German prisoner-of-war camps, most of them for the rest of the war. Three soldiers managed to escape and to return to England via Spain.

On March 29th Campbeltown exploded, destroying the southern dock gate for good. The military objective was achieved. In hindsight, the moral objective, to tell the world that Britain was still on its feet and fighting, was possibly the more important one. As a major of Saint-Nazaire said at one of the remembrance ceremonies, this raid was the first sign that gave the French people the hope that the German occupation might end one day.

The Op. Chariot monument comprises a menhir with a memorial plate and the 12-pounder gun from the destroyer HMS Campbeltown. Every year on March 28th a ceremony takes place at this spot (which is, incidentally, not far from the place where the German headquarters were located at the time of the raid). The ceremony is well attended by veteran organisations, representatives from the armed forces of Britain, France and Germany, school classes, and citizens of Saint-Nazaire. An official function is held afterwards at the town hall, and an additional Breton remembrance meeting at the Old Mole (I will come to that later). Among the veteran organisations attending is the (British) Saint Nazaire Society, of which all participants of the raid are automatic members.

Did you notice that the barrel of Campbeltown's gun is not quite straight? It was bent by the force of the explosion that destroyed both Campbeltown and the dock gate; the gun was only found many years later in the mud of the harbour, hundreds of metres from the dock.

We will encounter more places that remind us of this raid when we enter the harbour area. For now, I turn east again; we are now at the foot of the western jetty of the avant port, a sheltered area in front of a lock, which is where we will go next.

A look from the western jetty back towards the beach; take the excursion if you like the view.

The Loire estuary from Saint-Nazaire to Nantes

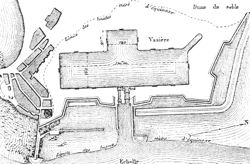

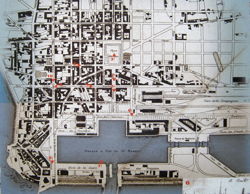

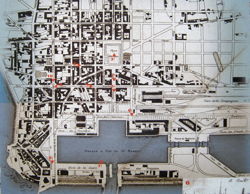

The first harbour basin and the old mole (about 1860, North is to the right of the map)

Same area, same time, but seen from the North

Similar view today ("zoomed in" a bit): Saint-Nazaire basin, new entrance with swing bridges, east jetty of the avant port

This map shows the two basins before the new entrance was built. The lock between the basins was later removed and replaced by a rotating bridge.

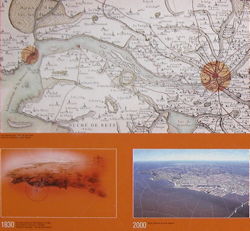

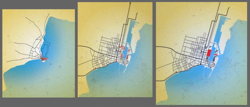

Development of Saint-Nazaire: Pre-1800, about 1931, 1945

The Saint-Nazaire basin, the new entrance when it was "new", and the power station

Standing in front of the fire station, looking east: lock gate, bridge and power station. The white tower to the left is the new harbourmaster's office. Compare the same view as it was in 1908!

Southern lock gate, the rotating bridge nearly open; the building is the old harbourmaster's office, today a fire station.

Boats entering the lock from the avant port

Fishing vessels waiting in the lock

Something big enters the new entrance lock

A look towards the Saint-Nazaire basin (north) with the swing bridge moving up

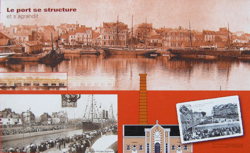

Up to 1945, the story of the development of Saint-Nazaire has been mainly the story of its harbour and dockyard area. On our walk, we are now approaching the oldest part of the town, the former peninsula where fishers, seamen and Loire pilots had been living since medieval times. In the 1830s the first steps were taken towards the building of a harbour: the Old Mole, finished in 1835, provided the first loading and unloading facilities, and the Saint-Nazaire basin (1847) was the first real harbour basin of the town. Its entrance looks eastward and has a lock to make the basin independent of the tide. In 1881 a second basin (Penhoët basin) was ready, but by this time the existing ("old") entrance to the basins was too small for modern ships. A larger entrance was needed, again with locks to keep the basins on a constant level; this "new entrance" was opened in 1907. Since it faces south, directly into the deep-water channel of the Loire estuary and thus relatively open to wind and waves, two jetties were added to shelter the entrance from wind and waves; the area enclosed by the jetties is called avant port ("before the harbour"). Both entrances are still in use today.

From the foot of the jetty we look right into the avant port. A few steps bring us to a small building (the former capitainerie, the harbour master's office, now a fire station) and to the rotating bridge across the lock. Have a look at the levers and gears that move the lock gates, they are massive indeed.

Before we continue, we may take a few minutes to see the lock in operation. With a bit of luck, you can see big and small ships enter and leave and even see the swing bridge at the northern end of the lock in operation.

The power station…

…with the anchor of Jean Bart (not yet in place in the 2002 image above).

Pumping machinery inside the power station

The sanitaire maritime building

To the left, a new building in the Old Town (built 2009); the crossroad to the right leads to the eastern jetty.

A look along the eastern jetty: Square dip-fishing nets

Peeping into

other people's business

In 2002, some German bunkers on the jetty were still used as stores.

The tips of the avant port jetties; in the background, the beaches of Villès-Martin

A view of the Loire; in the mist, the eastern coast of the estuary.

The building with the large chimney beyond the bridge is labelled usine elevatoire and usine electrique; it had the double functions of power station and pumping station to fill the lock. It is no longer in use, but you can see some of the remaining machinery through the door glass; there are plans to convert the building into a museum or an art centre. In front of its western wall there is an anchor on display; it belonged to the French battleship Jean Bart, famous for its last-minute escape from the German occupation force in June 1940 (it did not use this lock, though).

For now, we leave the Old Town alone and to our left and continue east towards the eastern jetty. The building east of the the power station is the sanitaire maritime, a former hospital for seamen.

When we arrive at the crosswise road we see the small sea rescue service school to our left, but we turn right (southward) and take a stroll onto the eastern jetty of the avant port. It gives a nice view of the Loire and, from the tip with its lighthouse, a view along the coast. In good weather you can see Mr. Hulot's beach at St. Marc-sur-mer and even as far as Pornichet and La Baule. Beyond that, out of view, are Brest and the Channel.

The square dip-nets on the jetty are used for a traditional way of fishing. You drop the net to the sea ground, raise it after a few minutes and collect whatever fishes have been caught. Three to four dips used to provide enough for a family meal, but yields have gone down these days I was told. Still, you see these nets all along the coast of Brittany.

Note also the traces of tidal lift here in the Loire; the difference between low ebb and high tide is, on average, 5 to 6 metres. At low tide, large parts of the Loire estuary fall dry and become mudflats. Knowledge of these mudflats and the navigable channels enabled the Nazairiens to act as pilots for ships bound for Nantes.

The area between the base of the jetty and the power station is used by harbour-related business and looks a bit unkempt, as any such real estate would. In 2002 there were still bunkers at the foot of the jetty, put to a new use as storage rooms.

The old mole as it was in the 1820s…

…and today.

View from the tip of the mole; to the left the stairs that saved Michael Burn's life.

The Saint-Nazaire variant of the Breton flag flying on the Old Mole

Couples in traditional Breton garb

The church, with the pilot's station and the mole to the left (model in the ecomusée)

Today, pilots' boats still make fast at the Old Entrance or in the avant port.

The abolition of slavery sculpture; in the background, the 1975 Loire bridge

The ecomusée; in the foreground, a model of the ocean liner SS Normandie

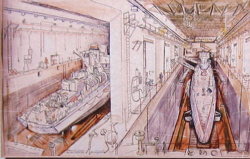

A model of HMS Campbeltown in the niche reserved for the history of Operation Chariot (no longer on display as of 2017)

Paquebots in the Saint-Nazaire basin

A postcard advertising trans-Atlantic ship journeys

The bridge over the old entrance leads to the sheltered lock

Espadon in the sheltered lock

Espadon: Depth rudder helmstands

Espadon: Torpedo tubes

And what is this? The shower cubicle.

It is strongly recommended that you do not open the wrong valves.

A look from the sheltered lock across the Saint-Nazaire basin towards the sheltered submarine pens

Moving northward again, just before we come to the foot of the Old Mole, we see an orientation table dedicated to to the comic strip character Tintin and his friends Milou (a dog that is called Snowy in the English translation) and Captain Haddock (a sea-dog famous for his inexhaustible supply of swear words). See below for more on them and the reason for their presence in Saint-Nazaire.

The Old Mole was the very first quay in Saint-Nazaire; it enabled ships, for example the pilot cutters, to moor and to load and unload cargo and passengers, but was soon reduced to just a landmark by the new harbour basins. The mole went under several names; in 1829, it was called mole d'abri ("protective jetty"), later jetée d'est ("eastern jetty"), and with the building of the avant port jetties it became the "Old Mole". The lighthouse at its tip has guided ships since 1829 and is still active.

The Old Mole was one of the designated landing spots for the commandos of Operation Chariot. Unfortunately, the pillbox bunkers on the mole with their searchlight and guns were never put out of action completely, leading to a great loss of life and eventually to a complete foundering of the departure plans of the commandos. On the other hand the steps at the mole saved the lives of some sailors and commandos who were swimming in the ice-cold water after their boats had sunk.

The mole is also the site of a special Breton remembrance ceremony for Operation Chariot, used not only to remember the raid but also the Breton tradition of the region. I also saw it used as the site of bidding farewell to the deceased by giving flower bouquets to the river.

At the foot of the mole were the pilot's station and a church; like virtually all buildings in the Old Town they were completely destroyed in the war. In the days before diesel engines, the pilot cutters were wonderful wooden sailing boats, in the Loire region often rigged as yawls. Jules Verne had a yacht that was built in Nantes along the lines of a pilot's boat; this boat (St. Michel II) is still sailing today.

Past the Old Mole, looking north, we see a sculpture in the water to commemorate the abolition of slavery. I am told that the steel girders represent the frames of a slave ship, and the figures stand for the stages in the abolition process. I confess that I would have had no idea what it meant without an explanation, but then I am not very good at that sort of thing anyway. I heard that some Nazairiens have the same problem with this sculpture, and in particular wonder what connection the abolition of slavery has with Saint-Nazaire.

Continuing north we come to the ecomusée (I could not find out the reason for the peculiar name), the town museum dedicated to the history of Saint-Nazaire and its surroundings. As of 2013, entrance is free, and I recommend to take the time to see it. It gives an overview of the complete history of Saint-Nazaire, with lots of models, maps and exhibits showing the industrial development of the town. Separate sections illustrate the fate of the town in both world wars. A video room shows episodes from the recent history; when I was there, they were running a film about the building of Queen Mary 2, current flagship of the Cunard line. The ship was built at the Alstom shipyard in Penhoët in, I was assured, record time. Unfortunately the shipbuilding business has taken a steep decline since, partly due to competition from the Far East, partly due to the enormous investment such a big ships constitutes; it seems that few companies currently see a business case for such an investment.

From the museum we continue to the North and come to the old entrance to the Saint-Nazaire basin; we will look at it in a moment, but for now I will just give a hint at the massive concrete structure ahead of us. It is a fortified lock, built by the Germans in 1943 to 44 to shelter their submarines when using the lock. Today the French post-war submarine Espadon (swordfish) is berthed there; it belongs to the museum (that is why I mention it here) and can be visited for a fee. Cross the old entrance bridge, walk through the tunnel in the concrete bunker and turn right for the entrance. Near the entrance to the Espadon exhibition you will also find the stairs leading up to the viewing platform on top of the bunker; we will go there in a moment.

Espadon is a conventional (diesel-electric) submarine that was in service for the French navy from 1960 to 1985. The Narval-class submarine is 78 metres long with a displacement of 1600 tons (1900 tons submerged). In active service it travelled 650.000 km and spent 33796 hours submerged.

If you are interested in submarines or naval technology I recommend a visit; you can move rather freely through the ship, and most of the installations and controls are still there.

A view of the Old Entrance from the roof of the submarine bunker across the Saint-Nazaire basin

The Old Entrance, seen from the East

A view northward from the mouth of the Old Entrance showing the Loire bridge

The southern gate of the Normandie dock, as seen from the Old Entrance

View from the panoramic terrace on top of the sheltered lock: Southward, the museum and the Old Mole.

View from the panoramic terrace on top of the sheltered lock: Down, the Old Entrance.

From a certain point of view, the red and white patterns on the buildings and silos begin to make sense. A nice and slightly eerie effect.

A view at the southern gate of the Normandie dock

Riveters at work in a Saint-Nazaire

shipyard

SS Normandie leaves the forme ecluse Louis Joubert, aka Normandie dock, in 1935.

The Normandie dock seen from the northern gate, empty…

…and occupied. Alas, the shipbuilding contracts become fewer and fewer.

Close-up view of the northern dock gate

The southern dock gate with the camber used for winding it open.

Dockside

Pump casings on a scrap-iron heap.

Such pumps, only bigger, are used to fill and empty the dry dock.

The rotating bridge between the Saint-Nazaire and Penhoët basins. In 2002, the Caserne des Douanes was still there.

A look from the bridge, southward along the length of the Saint-Nazaire basin

Now we come into the heart of the dockland, with the huge forme ecluse Louis Joubert (Normandie dry dock) as our focal point. We enter across the bridge of the "old" entrance; this is the original entrance to the first harbour basin, and the lock is still in use today (with new machinery, of course, a complete overhaul was done in 2002). When this entrance became too small for the ships, the new entrance we saw earlier was added; the Normandie dock became another, still bigger entrance (leading into the Penhoët basin), and in World War 2 another, massively sheltered lock was added parallel to the original old entrance. This sheltered lock is now the last home for the submarine Espadon (see previous section); its original task was to provide an access to the Saint-Nazaire basin and the submarine pens that was sheltered against air attacks; in locks, ships were quite vulnerable for some minutes.

From the old entrance we can see the southern gate of the Normandie dock, labelled "defense de s'accoster", i.e. "do not moor here". If the Germans would have had the bright idea to add that advice, would it have prevented Campbeltown ramming the gate? Probably not, though it might have worked against a German attack; they say that in Germany revolutions have failed because of a "do not trespass" sign on a strategically situated piece of lawn.

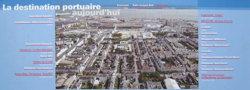

The view from the panoramic terrace is quite interesting. From there, you have an excellent view to the Saint-Nazaire basin, new entrance and avant port to the South, the submarine bunker and the town centre to the West, the Penhoët basin, dockyards and the town of Penhoët to the North and the old entrance, the Normandie dock and the Loire estuary to the East. When looking at the buildings and silos around the harbour basins, you may have noticed red geometric shapes, apparently painted randomly on the facades. From a certain point on the platform, they fall into place like a jigsaw puzzle and combine into a pattern of triangles spanning the northern sector. A playful way to add an attraction to this otherwise very commercial area that I appreciate, though I learned that not all Nazairiens do.

Next, we will take a look at the Normandie dock. The dock itself is fenced off; the best view of the southern gate, its winding machinery and the pump house is from the panoramic platform, and you can see into the dock itself from its northern end. To get there we proceed along the quay of the Saint-Nazaire basin (Av. des Frégates) and turn right when we reach the northern gate.

The Normandie dock is a dry dock that doubles as a lock, connecting the Penhoët basin with the Loire. It was built to help with the construction and equipment of SS Normandie, latest in a line of famous ocean liners built in Saint-Nazaire. Building the Normandie began in January 1931, and the hull was launched in October 1932; even the French president Lebrun attended the launching ceremony. Equipping the ship and finishing the interior took another 2.5 years, and from 1934 she was laid up in the Normandie dock (officially forme ecluse Louis Joubert, i.e. Louis Joubert lock) that was custom-built for this ship. SS Normandie won the Blue Riband (ruban bleu in French- we will encounter the expression again) for the fastest crossing of the Atlantic on her maiden voyage in 1935.

The Normandie dock is big– 350 metres long, 50 wide, 15 deep; when filled, it holds 260,000 tons of water. The gates are huge "caissons", massive box-like structures on rollers that can be drawn back into recesses ("cambers") to open the dock. We are standing right on the northern gate now, on the sidewalk of a 2-lane street that runs across the caisson: This "box" made from riveted steel profiles is 51 metres long, 11 thick and weighs more than 4000 metric tons (see this this image on the Saint Nazaire Society web site). The completion of the dock in 1934 was the final step of nearly 100 years of re-shaping the Saint-Nazaire waterfront.

Operation Chariot set out to destroy precisely these gates, the southern one by the explosive charge in HMS Campbeltown, and the commando demolition team of Lt. Brett was expected to take care of the northern one with specially-shaped, man-carried explosive charges placed by hand. An optimistic proposition indeed, just look at the structure you are now standing on!

For good measure, other demolition teams were to destroy the winding apparatus for opening the gates and the pumps needed to fill and drain the lock chamber (a process that takes 14 hours). This special machinery alone would take months to replace and would have rendered the dock inoperable even if Campbeltown's charges had failed.

But how do you destroy such a structure, if the first attempt is the only one you will get? Well, it helps if you have an almost-twin structure at home, in this case the King George V dock in Southampton. The British had complete plans how to destroy this dock in case of a German invasion, and these plans helped a lot in the planning of Chariot. Capt. William Edward ("Bill") Pritchard of the Royal Engineers was one of the officers responsible for planning the demolitions; he accompanied the raid as part of the "demolition control team", but did not live to see the final success of his planning; he was killed in the maze on the Old Town in the night of the raid.

The commando teams succeeded with the winding huts and the pumps, but failed at the northern gate because of German resistance; Campbeltown exploded shortly before noon on March 29th and took the southern gate with it as well as a few hundred sight-seeing German officers and troops, and delayed-action mines fired by MTB 74 exploded in the afternoon of Monday, March 30th, damaging the outer lock gate of the old entrance and causing panic with the German troops. The Normandie dock was destroyed in a few hours in March, 1942; it would not be in working order again until 1948.

The Normandie dock is still in use today; unfortunately, the orders to refurbish cruise liners or to build new ships have gone down these days, and it has been some years since the last ship was laid up in the dock. The general decline of European shipbuilding has left its traces in Saint-Nazaire, and the empty docks and slipways are a sad sight indeed. Shipbuilding has always been an industry with a lot of ups and downs, and Saint-Nazaire also has a history of periods of unemployment and decline; the "hunger march" to Nantes (March 1933) and the strikes of 1936 were caused by periods unemployment and exploitation. Saint-Nazaire has weathered those storms; I am confident that it will find ways to cope with today's problems as well.

Before continuing northward to the town of Penhoët, we make a small detour to the swing bridge that separates the Saint-Nazaire and Penhoët basins. The bridge can be swung open to allow a passage between the Saint-Nazaire and Penhoët basins. South of the bridge is a harbourmaster's yard with buoys and other material for repair. Across the bridge we see industrial structures, silos and storage buildings; the Caserne des Douanes (customs' offices), part of which was still standing west of the bridge in 2002, has now been demolished completely and has robbed the area of a historic landmark.

A recent addition to the bridge is a billboard showing Hergé's comic strip characters Tintin and Captain Haddock on their search for their kidnapped friend Prof. Tournesol. Captain Haddock remarks "All in all, we did not make any progress at all." Maybe they did not; we certainly did, as far as our walk is concerned.

The opposite view, northward from the roof of the submarine bunkers, shows the bridge and the

Penhoët basin.

Buoys waiting to be put to sea.

The working yard of the port authority

"Beware of stray paint"

A Turkish grain carrier moored in the

Penhoët basin

On the way to Penhoët: A gallery of cranes.

Big portal crane across a dock

Dockside "hammerhead"-type crane

Portal crane for cargo

Dockside cargo crane (blue) and heavy-duty sheerleg crane (red-white)

We will now proceed towards the town of Penhoët at the northern end of the Penhoët basin (or rather the other way round, the town was there a long time before the basin). The way leads through more dockland area and along quays, some of which are freely accessible (if you ignore the "do not trespass" signs); towards the northern end of the basin we have to make a detour to go around slipways and docks. The crane is the signature animal of the area, visible everywhere on the wayside and over the roofs, and I invite you to view a gallery of a few types I saw on my way to Penhoët.

The Penhoët dockside

Penhoët, Rue des Chantiers

Mural reminding of the airplane building tradition of Penhoët

A disused public bath in Penhoët, adjacent to…

…the market.

Back to Saint-Nazaire along the railroad tracks.

A look back towards the Normandie dock with a cruise ship put up for refurbishment. It is 2002, the Caserne des Douanes is still standing.

The town of Penhoët begins where the Penhoët basin ends. The town is small, and there are few places from where you cannot see a dock or crane. In addition to the shipyards, it has been connected to the airplane industry for a long time, and many streets near the market place are named after pilots or aviation pioneers. Today, the traditions is kept up by the Airbus Industries site and the airport east of Penhoët.

I went as far as the covered market, but as it was Sunday, it was closed, and generally there was not a lot of life in the streets. I went back towards the Av. de Penhoët quayside; at this point the railway line to Nantes splits into an branch that serves the quays and the passenger branch that curves westward to the current Saint-Nazaire railway station. This branch is new; until World War 2, the quayside branch served passengers and cargo alike, as we shall see later.

I cross the rails via a foot bridge to the Rue René Cassin, and then again to the Rue Henri Gautier that leads straight down right to the Place Quatre z'Horloges and the beach. However, for the next kilometre or so it is a bit dreary and quite "industrial", so I turn west towards the railway station and the new town centre.

The railway station at the northern end of the Av. de la Republique. The sculpture resembles a ship's propeller.

Old and new. Massive construction work goes on all over the town (Rue Henri Gautier (?), 2013).

The old cemetery

A cosy-looking hotel at the Rue Marceau

Another one that looks inviting

The dolmen on a small square near the centre of the new town

Buildings old and not-quite-new

The town in the grip of the caterpillar

Overview of planned and completed development of the new town

Ruban Bleu, the latest shopping centre on the site of the former Place Marceau

It looks good in the evening sun

A ferris wheel being set up in front of the Ruban Bleu

Reflections of a ferris wheel

What remained of the Gare d'Orleans in 2002

The new theatre has been merged with the old station

Industrial classicism vs.

modern colourful sobriety.

This map of shortly before 1900 shows how the railway ended directly at the harbour basins.

The front of the Gare d'Orleans in an old image…

…and as a model in the ecomusée.

Saint-Nazaire has been connected to the railway network since 1857. The old station was near the docks, and what is left of it after the war we will visit later. The modern station was built in the 1950s as a replacement, and today it serves local lines to Nantes and Pornichet as well as long-distance TGV trains. It is a simple, no-nonsense structure; outside, at the Place Pierre Semard, is a bus terminal for the local transport authority. Immediately east of the station the N471 road, the main long-distance connection into the town, crosses the rails and continues in a straight line as the Av. de la Republique, the main axis and longest shopping street of the town, that ends after nearly 1.5 km at the town hall.

However, I propose to take a detour to the Cimetière de Toutes-Aides at 35 Bd. Victor Hugo, one of the six cemeteries of Saint-Nazaire. It has a central rondel; tradition dictates that the most important families of the town got the burial sites at or near this rondel, so you can see which families were deemed most important when the sites were allocated.

We continue back into the commercial centre of the town, past the large market hall at the Place du Commerce back to the Av. de la Republique and south to the Paquebot shopping centre. One of the small bakeries there offers a really good flan (but then, many others do so as well).

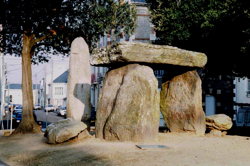

I continue eastward along the Rue Albert de Mun and turn left at the Rue du Dolmen that leads to the Square du Dolmen where we see, as you may have guessed, a dolmen, a neolithic burial site also known as dolmen de trois pierres (literally 3-stone dolmen, which is quite correct).

It is not really important which roads you actually use, as the town is built on a rather strict pattern of orthogonal roads, and it is hard to get lost if you keep track of a few landmarks. Most buildings are small, 2- to 3-storey affairs in various states of repair; shabby-looking buildings that are clearly part of the 1950s construction program mingle with houses that are beautifully re-constructed in their original, pre-war style. Reconstruction has been going on all over the town both times I was there, with street repairs, old building being restored to former beauty and new buildings replacing older ones or filling gaps. And the town administration is clearly determined to give Saint-Nazaire a very modern look wherever possible; I believe they are trying to shed the "bunkers and shipyards" image to that of an active, up-to-date and culturally interesting town that offers a home for arts and enterprises in a style that fits the 21st century. We are just arriving at two exemplary buildings, the new Ruban Bleu shopping mall on the site of the former Place Marceau, and the theatre built on the site of the old railway station.

Ruban Bleu is just a modern shopping mall, nothing special (but I am no expert for shopping malls, I rather hate the places) except for its site between the town centre and the harbour, linking them, attaching the harbour more closely to the town centre than it was before. The large square between Ruban Bleu and the submarine bunker is used for fun fairs and other events; I had the good luck to watch a ferris wheel set up and could take an aerial view of the town from its gondolas.

The theatre also creates a link, in this case between old and new. Before the war, the railway ended more or less on the harbour quay, and the area west of the Saint-Nazaire basin was one huge railway shifting yard. The station was called Gare d'Orleans, giving a hint at the primary connections possible from here; it had a "gare de voyageurs" and a "gare des marchandises", i.e. a travellers' and a cargo section. Travellers could walk directly from the platform to their ship, less than 200 metres away, and the offices of the Compagnie Transatlantique were directly adjacent to the station.

The station of 1857 was a magnificent building, as you can see from the images and the model you can see in the ecomusée. After the war, all that remained was the main entrance front, standing alone in a desert of ruins and unused rails. The rails have been removed by now, they only reach as far as the middle of the Penhoët basin and are only for used cargo, a supermarket is in the place of a former parking lot, and the new, very modern theatre "Le Fanal" (the signal) has been built next to the remains of the station building, which has been integrated with the theatre to form a

big cultural centre.

Like with the pieces of a puzzle, the town completes itself according to a new image and a new plan, filling gaps, occasionally removing a piece that does not seem to fit any more and replacing it with something new. An ongoing process, and certainly interesting to watch.

A massive block of concrete dominates the harbour…

…the only structure left standing in a field of ruins after the war.

The business end- the sheltered submarine pens seen from the Saint-Nazaire basin

The reverse view towards the sheltered lock

Built to stand a 1000 years of crumbling

The gaudy mermaid

Well-sheltered shops and bistrot

Top view: Roof with visitor's ramp

Original use…

…and re-use

On the roof: An art gallery…

…a sundial…

…and a view. Looking north towards Penhoët…

…and south towards the new entrance.

A beautiful morning, seen from the bunker

We have seen it from nearly every point of our walk, now we finally arrive there: the big submarine bunker on the western quays of the Saint-Nazaire basin. A block of concrete 300 m wide, 130 m deep, 18 m high, built and expanded from 1941 to 1942, providing 14 berths sheltered against bombs by a roof 8 metres thick, with anti-aircraft gun and searchlight platforms on top. As a side note, this roof was only hit by one single bomb in all the 50 air raids the Allies sent to Saint-Nazaire, which illustrates the universally abominable accuracy of WW2 bombing.

The priority after the war was to build new homes for the 40,000 people from Saint-Nazaire who had been evacuated during the war. When that was done, the Nazairiens thought about how to get rid of the monster in the middle of their town, but to their dismay they found that blasting it to pieces would probably also flatten most of the adjacent new buildings. Ho-hum. Well, they thought, if you cannot get rid of it, press it into service; they started to do some repairs and began to use the place. Today, the tourist office is there, a bookshop, and a bistrot. The berths are for hire to yachtsmen, and other rooms are used for temporary exhibitions. The open space west of the bunker is adorned by a sculpture of a gaudy (if slightly frog-mouthed) mermaid that provides a nice contrast to the grey-brown concrete. The bunker roof is accessible for visitors via a ramp and is used as a viewing platform, an open-air exhibition and several arts projects.

I recommend that you take the time to go onto the bunker roof to see the view, and to snoop around in the interior of the bunker. The bookshop has a wide range of books as well as music and videos, and specializes a bit (aside from the obvious Saint-Nazaire souvenirs) in "things Breton".

Blasting the bunker immediately after the war would have been difficult, but time conquers all. The 480,000 cubic metres of concrete are crumbling at an alarming rate today, and a Nazairien who spoke to one of the German architects of the bunker told me that this architect would give the bunker another ten years, at most. Thus, over the next years the question could be whether to save or to finally discard the thing, certainly an interesting decision to take.

A French frigate at the pier in front of le frigo; her crew attended the Op. Chariot remembrance ceremony in 2013.

Fishing vessels in the Saint-Nazaire basin

Across the swing bridge to the eastern quay and the Old Town

A sea tug

Le frigo and the submarine bunker seen from the eastern quay

Fishing vessels on the eastern quay

Warehouses and laid-up pilots' boats on the eastern quay (view from the Old Entrance panoramic terrace)

Fishermen cleaning their lobster traps

The Old Town seen from the Quai de la Vieille Ville

How the nucleus of Saint-Nazaire developed

A model of the 19th century Old Town (ecomusée)

Detail of the model: Houses south of the Old Mole

The Old Town, hastily rebuilt after the war

A passage as it looked in 2002

Houses change, people don't: Playing boule in the Old Town. The building is part of the 21st century reconstruction.

Back to the new town; the "Bridge of Memories"

A house at the Rue du Parc à l'Eau

A view towards the re-built church

Church and Place Quatre z'Horloges

A side door of the church

Flaming house on the way back to the town hall

Outside the bunker again, we turn south towards the harbour basin again. The big cuboid building next to the bunker is le frigo, a cold storage built in 1917 to store the supplies for the US troops as they entered the Great War; it is still in use today.

We walk around the basin and use the swing bridge across the new entrance to get from the Quai du Commerce (west) to the Quai de la Vieille Ville (east). The bridge is interesting in itself, maybe you can wait to see it opened for ships moving into and out of the new entrance lock. All around the harbour basins there are tugs, fishing vessels and pilots' and SAR boats, but this is only a faint echo of the busy port that was here in the 1920s and 30s. From this basin, the "packet boats" and cargo ships left for North and South America. It must have been a busy and beautiful place at the time!

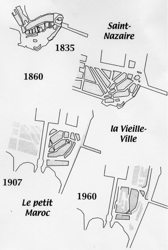

South of the basin we are close to the oldest part of Saint-Nazaire again; we passed the Old Town on our way from the new entrance to the Old Mole already, now we will take a closer look at it. Before the harbour basins were built, it was a peninsula and it was large enough for Saint-Nazaire before the 19th century; originally it was a fishermen's village, then the Old Mole and the pilot station were built (about 1835); by 1860 the Saint-Nazaire basin was enclosed, and the Old Town became a warren of small houses and narrow lanes. When the new entrance was built (1907), part of the Old Town was razed for the new structures, but the rest remained just the maze it had been before. In World War 2, the German occupants thought the confusing quarter might become a nest of the resistance and evacuated and destroyed it; Allied bombs took care of what was left. In the 1950s it was rebuilt hastily with small, 2- to 3-storey row houses; most of these houses have by now been replaced with modern, comfortable buildings. We walk through the Rue de la Vieille Eglise to the quay of the new entrance.

The name "Petit Maroc" is not the historic name of this part of the town. From the time Saint-Nazi are became big enough to need names for different quarters until after World war 2 it was always known as vieille ville, the Old Town; the name Petit Maroc appeared in the 1930s for the first time. Its origin is rather unclear, but probably it has nothing to do with Morocco (though one hypothesis says that fishermen lived here who worked off the Barbary coast). The name may be a malapropism of an old Breton name for the place (Ti war roc'h is Breton for "the house on the rock") or of the name of the 5th century Breton king named Waroc'h, but this is not proven either. Whatever the origin, the current administration seems to think the name tres chic, even if historians object strongly to its use.

From the new entrance quay we see the swing bridge once more. When the commandos of Operation Chariot realized that their transport had gone, those who were still able to fight tried to escape the trap of the harbour area across this bridge, in the hope to gain the open ground outside the town and possibly evade and escape back to Britain. It was dubbed the "bridge of memories" because of the bitter and desperate fight for this escape route in the night of the raid. The commandos won the bridge, only to be rounded up in their hideouts later that day. In the first years after the war, the Chariot veterans paraded across this bridge on the raid's anniversary days.

We are near the end of our walk. Crossing over to the western side of the new entrance we come to the Boulevard René Coty and to the Place Quatre z'Horloges, the place of the four clocks; if you like, take a café in the Grand Café there. The Rue du Général de Gaulle leads us past the church (heavily damaged in the war, but re-built) and back to the town hall.

Me and Saint-Nazaire

You may have noticed that I like the town and that I am somewhat enticed by its history. For me, Saint-Nazaire was, it first, just an abstract place where a historic event (the Chariot raid) took place. When I was there, it became a real place with real people living there, and when I got to know some of them on my second visit in 2013 my interest became even stronger. Some Nazairiens took the time to tell their stories and even gave me a guided tour of the town, for which I am deeply grateful. I hope that this small guided tour may have given you an impression of Saint-Nazaire, and maybe it has even made you curious enough about the town to visit it yourself.

I will certainly be back.

01:28: The Eastern jetty of the avant port. At that time Lt.-Cdr. Beattie struck the German flag, hoisted the White Ensign and began to return fire.

The Old Mole, the landing place of about half of the commando soldiers. In the background, an outbound ship passes Saint-Nazaire for the Loire estuary.

Again, the Old Mole, seen from a spot where a German gun emplacement was in 1942, at point-blank range to the disembarkation site. On the mole itself there were a manned pillbox and a searchlight that foiled the landing attempt.

The southern caisson gate of the Normandie dock. H.M.S. Campbeltown rammed this gate at 01:34, "four minutes late", as Beattie remarked.

The old entrance to the Saint-Nazaire harbour basin. L/Col. Newman

and his HQ staff disembarked there and established headquarters in a building to the left. The bridge was the scene of heavy fighting, as it was the withdrawal route of the troops who had demolished the dock installations.

The swing bridge on the Quai de la Vieille Ville. When the commandos realized that their boats were gone, they stormed this bridge against heavy German resistance shortly after 03:00 h to try and escape via land routes. Nearly all of those who survived the attempt were captured that same night.

The new entrance lock, a view to the North to the swing bridge. The demolition of this lock failed completely, as the troops assigned to this target never made it to the shore.

The new entrance lock, seen towards the South and showing the swing bridge

before the avant port basin. To the left is the Old Town, in 1942 a maze of small streets in which some commandos tried to hide.

A French frigate made fast in the Saint-Nazaire basin at the Quai du Commerce. Their crew attended the Operation Chariot remembrance ceremony later that day.

I took these pictures on March 28th, 2013, between 01:28 and 02:18 in the morning– exactly the date and time of the Chariot raid, plus 71 years. I had just come from the annual meeting and dinner of the Saint Nazaire Society and wanted to spend that night out in the harbour area.

I am not an expert in night photography, but I think the pictures are still beautiful. All of them were taken with a Nikon D80 digital SLR camera without a tripod, I just stabilized it against anything that looked as if it would help, and using only "available light".

The orientation table near the Old Mole

#1: And a few minutes later… "Now, finally, tell me where we are going, captain?" "To Saint-Nazaire!"

#2: Next morning…

#3: "All in all, we did not make any progress at all." "That's right."

#4: "Look, a ship to South America… just to think that the kidnappers may be aboard…"

#5

#6

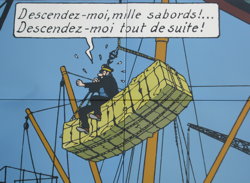

#6: "Put me down again, blistering barnacles! Put me down again immediately!"

Tintin is a comic strip character created by the Belgian artist Hergé (a nom de plume of George Prosper Remi, created from the reversal of his initials G. R.). The adventure of "The Seven Crystal Balls" (Les Sept Boules de Cristal) takes Tintin to Saint-Nazaire, together with his dog Milou (Snowy, in the English version) and his robust companion Captain Haddock; they are in pursuit of the kidnappers of their friend Professor Cuthbert Calculus (Professeur Tryphon Tournesol). In several panels of this adventure you can clearly recognize views of Saint-Nazaire and Penhoët as they were in the 1930s, some years before the adventure was first published. Hergé often worked from photographs to create his drawings, and we must assume that he did so in this case because the views are pretty accurate, though not necessarily corresponding precisely to the presumed route our heroes took in the course of the adventure.

The society Les 7 Soleils, based in Saint-Nazaire, has started in 1986 to erect large reproductions of the comic strip panels in both towns and thus created the "parcours Tintin". When I was there in 2013, there were 6 such panels, and one orientation table at the foot of the Old Mole; I believe there are plans to extend the parcours. The panels are numbered in the sequence in which they appear in the comic book, the panel numbers in my map match the numbers in the official description.

Remarks:

As the author of this page I take no expressed or implied responsibility for the content of external links; opinions expressed on such pages are not necessarily mine. The web space provider is not responsible for the contents of this page or any linked pages.

Written and published by Lutz Pietschker. Please send comments about technical problems to the

site master.

-Made with a Mac!-

, last change 2017-05-28